We want your input on which seminars to run

Please read the seminar descriptions below and email Jordan Goldstein (jgoldstein@tikvahfund.org) or Anton Sack (asack@tikvahfund.org) to tell us which seminars you want to see us run again.

Great American Speeches

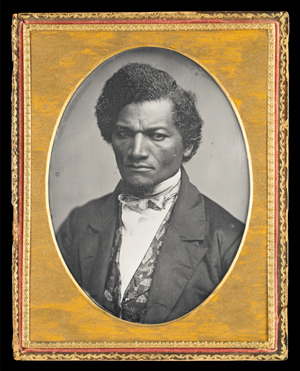

Frederick Douglass: What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?

with Dr. Samuel Goldman, George Washington University

As virtually every American today understands, without the need for any argument, the existence of slavery was a stain on the American Republic from its Founding. It also embarrassed our alleged devotion to the principles of human equality and unalienable rights, principles that had been presented in our birth announcement as truths by which we Americans define ourselves in declaring that we hold them to be self-evident. No American in our history has exposed our hypocrisy more powerfully than did Frederick Douglass (circa 1818–1895), a one-time slave who became a great orator, statesman, and abolitionist. Douglass made the case best in his famous Fourth of July oration (here excerpted), delivered on July 5, 1852 before the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester, New York. Yet as remarkable as his indictment is his vigorous defense of the Constitution and of the American experiment

As virtually every American today understands, without the need for any argument, the existence of slavery was a stain on the American Republic from its Founding. It also embarrassed our alleged devotion to the principles of human equality and unalienable rights, principles that had been presented in our birth announcement as truths by which we Americans define ourselves in declaring that we hold them to be self-evident. No American in our history has exposed our hypocrisy more powerfully than did Frederick Douglass (circa 1818–1895), a one-time slave who became a great orator, statesman, and abolitionist. Douglass made the case best in his famous Fourth of July oration (here excerpted), delivered on July 5, 1852 before the Ladies Anti-Slavery Society of Rochester, New York. Yet as remarkable as his indictment is his vigorous defense of the Constitution and of the American experiment

Samuel Goldman is an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is also executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. His first book God’s Country: Christian Zionism in America was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 2018. His next book, After Nationalism was published in Spring 2021. Goldman received his Ph.D. from Harvard, and taught at Harvard and Princeton before coming to GW. In addition to his academic work, Goldman is a national correspondent at The Week and a contributing editor at The American Conservative. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

Frederick Douglass: Oration in Memory of Lincoln

with Dr. Samuel Goldman, George Washington University

Frederick Douglass delivered his “Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln” at the unveiling of The Freedmen’s Monument in Lincoln Park, Washington, DC on April 14, 1876. Douglass himself did not care for the statue, sculpted by Thomas Ball and showing a kneeling slave at Lincoln’s feet. During the unveiling, he was overheard complaining that it “showed the Negro on his knees when a more manly attitude would have been indicative of freedom.”

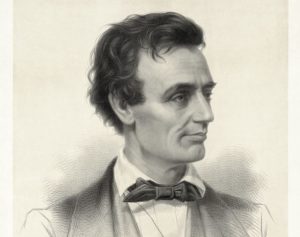

Abraham Lincoln: The Lyceum Address

with Dr. Leon Kass, American Enterprise Institute

One of Lincoln’s earliest published speeches, the Lyceum Address was delivered when Lincoln was just 28 years old and newly arrived in Springfield, Illinois. A little-known lawyer serving as a state representative, Lincoln spoke before a gathering of young men and women on January 27, 1838 about “the perpetuation of our political institutions.” Prompted by the murder of an abolitionist printer in Illinois two months earlier, he worried that Americans were increasingly inclined to take the law into their own hands. In the grip of strong passions, they were substituting vigilante justice for the justice of law.

One of Lincoln’s earliest published speeches, the Lyceum Address was delivered when Lincoln was just 28 years old and newly arrived in Springfield, Illinois. A little-known lawyer serving as a state representative, Lincoln spoke before a gathering of young men and women on January 27, 1838 about “the perpetuation of our political institutions.” Prompted by the murder of an abolitionist printer in Illinois two months earlier, he worried that Americans were increasingly inclined to take the law into their own hands. In the grip of strong passions, they were substituting vigilante justice for the justice of law.

Leon R. Kass, M.D., Ph.D., is the Addie Clark Harding Professor Emeritus in the Committee on Social Thought and the College at the University of Chicago and the Madden-Jewett Scholar Emeritus at the American Enterprise Institute. He was chairman of the President’s Council on Bioethics from 2001 to 2005. His numerous articles and books include: Toward a More Natural Science: Biology and Human Affairs, The Hungry Soul: Eating and the Perfecting of Our Nature, Wing to Wing, Oar to Oar: Readings on Courting and Marrying (with Amy A. Kass), Life, Liberty, and the Defense of Dignity: The Challenge for Bioethics, The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis, What So Proudly We Hail: The American Soul in Story, Speech, and Song (with Amy A. Kass and Diana Schaub), Leading a Worthy Life: Finding Meaning in Modern Times, and (forthcoming) Founding God’s Nation: Reading Exodus.

Abraham Lincoln: Cooper Union Speech

with Dr. Bryan Garsten, Yale

After his U.S. Senate defeat to Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in January 1859, Lincoln began considering a presidential run. Invited to speak in New York City by the clergyman Henry Ward Beecher (1813–87), Lincoln began drafting one of the longest and most important speeches of his political career. On February 27, 1860, the dark-horse candidate faced an audience of 1,500 spectators, including such luminaries as the editor of the antislavery New York Tribune, Horace Greeley (1811–72). The next day, 170,000 copies of the speech were in circulation through the newspapers, and less than ten weeks later, Lincoln secured the Republican nomination for president.

Bryan Garsten is Professor of Political Science and the Humanities, and Chair of the Humanities Program at Yale University. He is the author of Saving Persuasion: A Defense of Rhetoric and Judgment (Harvard University Press, 2006) as well as articles on political rhetoric and deliberation, the meaning of representative government, the relationship of politics and religion, and the place of emotions in political life. His writings have won various awards, including the First Book Prize of the Foundations of Political Theory section of the American Political Science Association.

Abraham Lincoln: The Gettysburg Address

with Dr. Diana J. Schaub, American Enterprise Institute

On November 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln (1809–65) delivered his most memorable speech at a ceremony dedicating the cemetery for the Union dead at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, site of the great victory in July of that year which marked a turning point in the Civil War. Lincoln used the occasion to offer his interpretation of the war and the reasons for which it was being fought. To do so, he revisits the Declaration of Independence, summoning the nation to achieve a “new birth of freedom” through renewed dedication to the founding proposition of human equality.

Diana J. Schaub is a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), where her work is focused on American political thought and history, particularly Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, African American political thought, Montesquieu, and the relevance of core American ideals to contemporary challenges and debates. Concurrently, she is a professor of political science at Loyola University Maryland, where she has taught for almost three decades. An expert in political philosophy, Dr. Schaub has lectured on a variety of topics and participated in conferences around the country. She has contributed chapters to multiple books on Shakespeare, liberal education, women, and religion, and she is the author of two books: “What So Proudly We Hail: The American Soul in Story, Speech, and Song,” coedited with Amy and Leon Kass (ISI Books, 2011), and “Erotic Liberalism: Women and Revolution in Montesquieu’s ‘Persian Letters’” (Rowman & Littlefield, 1995). Her monograph, “Emancipating the Mind: Lincoln, the Founders, and Scientific Progress” (AEI, 2018), is based on her remarks at the 2018 Walter Berns Constitution Day Lecture.

Abraham Lincoln: Second Inaugural

with Dr. Harry Ballan, Tikvah Fund

Lincoln, who presided over the successful prosecution of the Civil War, also gave deep thought to the war’s cause, meaning, and purpose, and also to what would be required to heal the nation after the war was over. In the Gettysburg Address (November 19, 1863), Lincoln had summoned Americans to rededicate themselves to the cause of freedom and equality. Here, in his Second Inaugural Address (March 4, 1865), invoking theological speculation and quoting Scripture, Lincoln offers an interpretation of the meaning of the war and summons all Americans to a new and more difficult public purpose.

Harry Ballan is Senior Director of the Tikvah Fund and Founding Dean of both the Tikvah Online Academy and the Abraham Lincoln Teachers Fellowship. Dr. Ballan holds a BA, MA, MPhil, and PhD from Yale University and a JD from Columbia Law School. He clerked for Chief Judge Wilfred Feinberg of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and was for many years a Partner at Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP, a leading international law firm where he is currently Senior Counsel. He has taught at several leading universities on subjects ranging from law and intellectual history to neuroscience, and was Dean of Touro Law School before joining Tikvah.

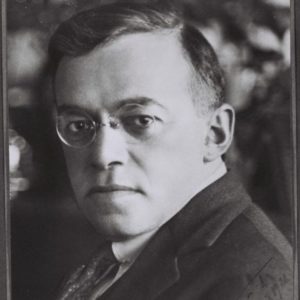

Booker T. Washington: Democracy and Education

with Dr. Diana J. Schaub, American Enterprise Institute

The son of an African American slave and a white planter, Booker Taliaferro Washington (1856–1915) was part of the last generation of Americans to be born into slavery, freed in 1865 as the Civil War came to a close. After working in salt furnaces and coal mines in West Virginia, Washington attended the Hampton Institute, a school in Virginia dedicated to educating freemen, and, a few years later, at the age of 25, became the first president of the Tuskegee Institute, an African American teachers college in Alabama. He headed the Institute for the rest of his life, using his position to write about and promote his views on race and civil rights. Washington’s books include, among others, The Future of the American Negro (1899), Up from Slavery (1901), and Working with the Hands (1904).

The son of an African American slave and a white planter, Booker Taliaferro Washington (1856–1915) was part of the last generation of Americans to be born into slavery, freed in 1865 as the Civil War came to a close. After working in salt furnaces and coal mines in West Virginia, Washington attended the Hampton Institute, a school in Virginia dedicated to educating freemen, and, a few years later, at the age of 25, became the first president of the Tuskegee Institute, an African American teachers college in Alabama. He headed the Institute for the rest of his life, using his position to write about and promote his views on race and civil rights. Washington’s books include, among others, The Future of the American Negro (1899), Up from Slavery (1901), and Working with the Hands (1904).

Great Zionist Speeches

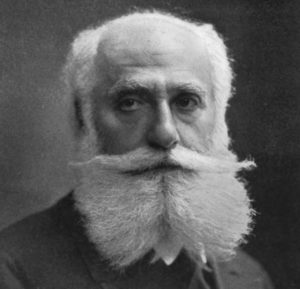

Max Nordau: Address at the First Zionist Congress

with Dr. Allan Arkush, SUNY Binghamton

Although Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau were both from Budapest, the two men met for the first time in Paris, in 1894. Nordau was by that time an international literary celebrity, the author of such controversial works of cultural criticism as The Conventional Lies of Our Civilization (1883) and Degeneracy (1893). He had traveled an immense distance from his Orthodox Jewish roots and, indeed, any affiliation with the Jewish people to become a cosmopolitan agnostic. His observation of growing European antisemitism had left him skeptical, however, about the possibilities for Jewish assimilation, and when Herzl began to espouse Zionism he found in Nordau a ready convert to the new idea. Nordau became Herzl’s right-hand man and the vice-president of the World Zionist Organization. A consummate orator, his speeches were the highlights of the early Zionist Congresses. According to the London Jewish Chronicle, his speech at the first Zionist Congress generated a “fever heat of enthusiasm among the delegates.” They interrupted him repeatedly with loud shouts of approval, and some of them wept openly as he described the contemporary travail of the Jewish people. His subsequent orations weren’t always accorded such a warm reception. The speech he gave in 1903 in support of the “Uganda Plan” (to follow up a British offer for a Jewish homeland in East Africa as a temporary substitute for Palestine) inspired one opponent to try to shoot him at a Zionist Hanukkah party in 1903. Nordau survived the attack, and lived long enough to witness the issuance of the Balfour Declaration in 1917.

Although Theodor Herzl and Max Nordau were both from Budapest, the two men met for the first time in Paris, in 1894. Nordau was by that time an international literary celebrity, the author of such controversial works of cultural criticism as The Conventional Lies of Our Civilization (1883) and Degeneracy (1893). He had traveled an immense distance from his Orthodox Jewish roots and, indeed, any affiliation with the Jewish people to become a cosmopolitan agnostic. His observation of growing European antisemitism had left him skeptical, however, about the possibilities for Jewish assimilation, and when Herzl began to espouse Zionism he found in Nordau a ready convert to the new idea. Nordau became Herzl’s right-hand man and the vice-president of the World Zionist Organization. A consummate orator, his speeches were the highlights of the early Zionist Congresses. According to the London Jewish Chronicle, his speech at the first Zionist Congress generated a “fever heat of enthusiasm among the delegates.” They interrupted him repeatedly with loud shouts of approval, and some of them wept openly as he described the contemporary travail of the Jewish people. His subsequent orations weren’t always accorded such a warm reception. The speech he gave in 1903 in support of the “Uganda Plan” (to follow up a British offer for a Jewish homeland in East Africa as a temporary substitute for Palestine) inspired one opponent to try to shoot him at a Zionist Hanukkah party in 1903. Nordau survived the attack, and lived long enough to witness the issuance of the Balfour Declaration in 1917.

Allan Arkush is Professor of Judaic Studies and History at the State University of New York at Binghamton and Senior Contributing Editor of the Jewish Review of Books. He holds degrees from Cornell University, the Jewish Theological Seminary, and Brandeis University. He is the author of Moses Mendelssohn and the Enlightenment and co-editor of Perspectives on Jewish Thought and Mysticism: Essays in Memory of Alexander Altmann. His numerous essays on modern Jewish thought and Zionism have appeared in Modern Judaism, Jewish Social Studies, Jewish Quarterly Review, Polity, and other periodicals and books. He is the translator of Moses Mendelssohn’s Jerusalem and Gershom Scholem’s Origins of the Kabbalah. From 2006 to 2009 he was the editor of AJS Perspectives, the magazine of the Association for Jewish Studies.

Hayim Bialik: Hebrew University Opening Address

with Dr. Leora Batnitzky, Princeton

When the Hebrew University was first proposed, Hayim Bialik became one of its most enthusiastic protagonists, for here he believed the old and the new, the Jewish and the supranational, would meet to blend in a contemporary but traditional Hebrew culture.

Leora Batnitzky is Perelman Professor of Religion and Chair of the Department of Religion at Princeton University as well as the Director of Princeton’s Tikvah Project on Jewish Thought. She is the author of Idolatry and Representation: The Philosophy of Franz Rosenzweig Reconsidered (Princeton, 2000), Leo Strauss and Emmanuel Levinas: Philosophy and the Politics of Revelation (Cambridge, 2006), and How Judaism Became a Religion: An Introduction to Modern Jewish Thought (Princeton). Her current project focuses on the conceptual and historical relations between modern religious thought (Jewish and Christian) and modern legal theory (analytic and Continental). She received a B.A. in philosophy from Barnard College, Columbia University and a B.A. in biblical studies from the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. Her M.A. and Ph.D. are in religion from Princeton University.

Ze’ev Jabotinsky: Testimony Before the Royal Commission

with Dr. Brian Horowitz, Tulane

In contrast to his usual audience consisting primarily of Jews, here Jabotinsky spoke before a group of British officials. In this case one need not perceive Jabotinsky’s politeness as an attempt to ingratiate with the powerful. To be sure, his demeanor reflected his desire to win over his audience, but it was also intended to display Hadar, the Revisionist principle of good behavior. Jabotinsky’s hoped to show that Zionist Revisionists embodied Western culture rather than violence or barbarism, which is how their opponents portrayed them.

In contrast to his usual audience consisting primarily of Jews, here Jabotinsky spoke before a group of British officials. In this case one need not perceive Jabotinsky’s politeness as an attempt to ingratiate with the powerful. To be sure, his demeanor reflected his desire to win over his audience, but it was also intended to display Hadar, the Revisionist principle of good behavior. Jabotinsky’s hoped to show that Zionist Revisionists embodied Western culture rather than violence or barbarism, which is how their opponents portrayed them.

Although he spoke to non-Jews, his speech repeated several themes that had preoccupied him of late. From the start, he invoked the “humanitarian aspect” of his appeal, his plea to “save the Jews of Europe.” Although every Zionist who appeared before the Commission drew attention to the plight of Europe’s Jews, nonetheless some bold aspects particular to Jabotinsky appear. For example, he challenged British officials to create a Jewish majority in Palestine or to return the Mandate to the League of Nations and let another country have a try.

The key theme in the speech is morality. In preparing his speech, Jabotinsky clearly considered the dilemma facing the Commission’s members: how to adjudicate the demands of the Jews with those of the Arabs. Only a higher moral imperative would sway their vote. Jabotinsky gave himself the task of explaining why Zionism was a moral project and as a moral project had to be defended by good people everywhere, including Britain’s government.

Brian Horowitz is the Sizeler Family Chair Professor of Jewish Studies at Tulane University in New Orleans. He is an award-winning and noted scholar of Zionism and Russian literature and the author of many books, including Vladimir Jabotinsky: The Russian Years (2020) and Russian-Jewish Tradition: Intellectuals, Historians, Revolutionaries (2017).

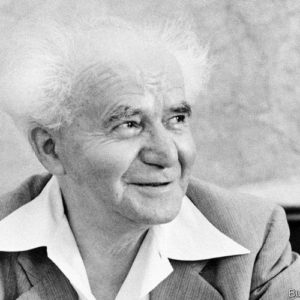

David Ben Gurion: The Needs of War

with Dr. Daniel Polisar, Shalem College

In 1946, as efforts to establish a Jewish state moved into high gear, David Ben-Gurion was convinced the Arab states would join the Arabs of Palestine in seeking to prevent a Jewish state from coming into being, and he asked for and received the Defense Portfolio of the Jewish Agency in addition to serving as the Agency’s overall leader. In that role, he sought to impress upon his colleagues that the war they would be fighting would require weapons and strategy well beyond anything for which they were prepared. After the UN voted on partition in November 1947, Ben-Gurion was the consensus candidate to serve as leader of the Jewish state and in his dual role as de facto prime minister and defense minister he sought to persuade his colleagues to put all available resources into the war effort, initially against the Arabs of Palestine and subsequently against the Arab states he was certain would attack. It was with this goal in mind that he addressed his colleagues in the Central Committee of the Labor Party on January 16, 1948, in a speech that is widely viewed as having a major impact on how the war was seen and fought on the Jewish side.

In 1946, as efforts to establish a Jewish state moved into high gear, David Ben-Gurion was convinced the Arab states would join the Arabs of Palestine in seeking to prevent a Jewish state from coming into being, and he asked for and received the Defense Portfolio of the Jewish Agency in addition to serving as the Agency’s overall leader. In that role, he sought to impress upon his colleagues that the war they would be fighting would require weapons and strategy well beyond anything for which they were prepared. After the UN voted on partition in November 1947, Ben-Gurion was the consensus candidate to serve as leader of the Jewish state and in his dual role as de facto prime minister and defense minister he sought to persuade his colleagues to put all available resources into the war effort, initially against the Arabs of Palestine and subsequently against the Arab states he was certain would attack. It was with this goal in mind that he addressed his colleagues in the Central Committee of the Labor Party on January 16, 1948, in a speech that is widely viewed as having a major impact on how the war was seen and fought on the Jewish side.

Daniel Polisar is the co-founder and executive vice president of Shalem College in Jerusalem, Israel’s first liberal arts college. He previously served as the president of the Shalem Center from 2002-2013 and also as its director of research, academic director, and editor-in-chief of its journal, Azure. From 2006 to 2009, he served as the founding chairman, within the Office of the Israeli Prime Minister, of the National Council for the Commemoration of the Legacy of Theodor Herzl. Dr. Polisar received his BA in politics from Princeton University and his PhD in government from Harvard University, where he was the recipient of Truman and Fulbright scholarships, as well as of a Mellon Fellowship. His research interests include Zionist history and thought, Israeli constitutional development, and the history and philosophy of higher education.

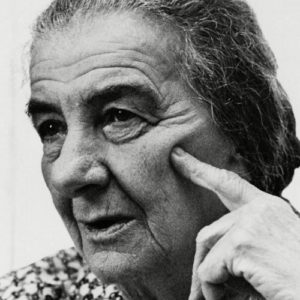

Golda Meir: Speech to the Assembly of the Jewish Federations

with Dr. Daniel Polisar, Shalem College

On January 22, Meir flew to New York, landing in a snowstorm. Shortly afterwards, she met with Henry Montor, the executive director of the United Jewish Appeal, the major fundraising organization of American Jewry, and together they decided she should attend the annual General Assembly of the Council of Jewish Federations, which was to be held in Chicago two days later. Palestine was not on the agenda of the Assembly, which was dominated by the routine issues of inter-faith relations and the situation within the Jewish federations. At the last moment Montor was able to get Meir included, but she was warned to make a short speech, not to be emotional, and not to make demands. In her characteristically independent fashion, she spoke at length (though without any notes), gave an emotional speech, and made enormous demands, telling her listeners they needed to provide at least $25 million—an astronomical sum at the time—to ensure that the Jews would win the war and establish a state. Montor, in describing the effect of her speech, said that “Sometimes things occur, for reasons you don’t know why. You don’t know what combination of words has done it, but an electric atmosphere generates. People are ready to kill somebody or to embrace each other. And that is still vivid in my mind, that particular afternoon…She had swept the whole conference.”

On January 22, Meir flew to New York, landing in a snowstorm. Shortly afterwards, she met with Henry Montor, the executive director of the United Jewish Appeal, the major fundraising organization of American Jewry, and together they decided she should attend the annual General Assembly of the Council of Jewish Federations, which was to be held in Chicago two days later. Palestine was not on the agenda of the Assembly, which was dominated by the routine issues of inter-faith relations and the situation within the Jewish federations. At the last moment Montor was able to get Meir included, but she was warned to make a short speech, not to be emotional, and not to make demands. In her characteristically independent fashion, she spoke at length (though without any notes), gave an emotional speech, and made enormous demands, telling her listeners they needed to provide at least $25 million—an astronomical sum at the time—to ensure that the Jews would win the war and establish a state. Montor, in describing the effect of her speech, said that “Sometimes things occur, for reasons you don’t know why. You don’t know what combination of words has done it, but an electric atmosphere generates. People are ready to kill somebody or to embrace each other. And that is still vivid in my mind, that particular afternoon…She had swept the whole conference.”

That speech had an enormous impact on the listeners, and since they headed the Jewish federations around the United States, they in turn played a crucial role in bringing Meir to their communities and assisting her in raising funds. Within a month she had secured $25 million, a week later she had commitments for $30 million, and by the time she came back to Israel in mid-March after a whirlwind, two-month visit, she had raised $50 million, double the seemingly impossible target she had set. This money was crucial as it was used to purchase weapons, especially from the Soviet Union’s satellite, Czechoslovakia, which played a decisive impact on battles as early as April. A second visit in May and June yielded an additional $50 million. Meeting her shortly after her return to Israel from the first trip, whose success stemmed in large measure from her speech in Chicago, Ben-Gurion told her: “Someday when history will be written, it will be said that there was a Jewish woman who got the money which made the state possible.”

Moshe Dayan: Eulogy for Ro’i Rotberg

with Dr. Allan Arkush, SUNY Binghamton

Kibbutz Nahal Oz was established in 1951 as the first Nahal (Noar Halutzi Lohem, i.e. Fighting Pioneer Youth) settlement. Like others that were to follow, it was designed both to cultivate agricultural land and to protect a sensitive border-point. Built right on Israel’s border with the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip, it was situated almost within sight of the newly created camps housing Arab refugees who had fled their homes in the course of Israel’s War of Independence. From the end of the war until the Sinai campaign in October of 1956, Palestinian infiltrators and guerillas, encouraged by the Egyptian authorities, had crossed the border, both to pilfer fields and to kill Israelis.

Kibbutz Nahal Oz was established in 1951 as the first Nahal (Noar Halutzi Lohem, i.e. Fighting Pioneer Youth) settlement. Like others that were to follow, it was designed both to cultivate agricultural land and to protect a sensitive border-point. Built right on Israel’s border with the Egyptian-occupied Gaza Strip, it was situated almost within sight of the newly created camps housing Arab refugees who had fled their homes in the course of Israel’s War of Independence. From the end of the war until the Sinai campaign in October of 1956, Palestinian infiltrators and guerillas, encouraged by the Egyptian authorities, had crossed the border, both to pilfer fields and to kill Israelis.

On the morning of April 29, 1956, a young kibbutznik, Ro’I Rotberg, went out on his horse to investigate reports of Arab infiltrators who were harvesting the wheat crop in Nahal Oz’s fields near the border. He was shot and killed, and his body was dragged back to Gaza. His mutilated corpse was returned to Israel by UN officials hours later. The IDF’s Chief of Staff, Moshe Dayan, who had met with Rotberg the day before he fell, decided to come to Nahal Oz to give the eulogy for him.

When Rotberg’s murderers were later apprehended, it turned out that one was an Egyptian police sergeant and the second was a Palestinian guerilla – a finding that underscored the collusion between the Egyptian security forces, which in principle should have been responsible for preventing such incidents, and the guerillas. Dayan’s oft-cited words on the circumstances and significance of Rotberg’s death have had a strong impact on the way Israelis view the dual needs of defense and construction down to this day.

Gideon Hausner: Opening Address at the Trial of Adolf Eichmann

with Dr. Daniel Polisar, Shalem College

Hausner’s opening statement was given over the course of three sessions on April 17 and 18, and it took several hours to deliver it. Despite Ben-Gurion’s concerns that Hausner might not rise to the occasion, the first segment of it is considered one of the most powerful and memorable speeches in Israeli history. Hausner succeeded in gripping the imagination of much of the country and placing the spotlight on Holocaust survivors, who previously had been reluctant to speak about their experiences. During Hausner’s remarks, 60% of the Israeli population age 14 and above listened to at least part of the broadcast, an astonishingly high figure. Moreover, in part because this opening had been so gripping, from then until the trial ended in August 1961, hundreds of thousands of Israelis, including large numbers of young people, were glued to their radio sets for hours every day.

Hausner’s opening statement was given over the course of three sessions on April 17 and 18, and it took several hours to deliver it. Despite Ben-Gurion’s concerns that Hausner might not rise to the occasion, the first segment of it is considered one of the most powerful and memorable speeches in Israeli history. Hausner succeeded in gripping the imagination of much of the country and placing the spotlight on Holocaust survivors, who previously had been reluctant to speak about their experiences. During Hausner’s remarks, 60% of the Israeli population age 14 and above listened to at least part of the broadcast, an astonishingly high figure. Moreover, in part because this opening had been so gripping, from then until the trial ended in August 1961, hundreds of thousands of Israelis, including large numbers of young people, were glued to their radio sets for hours every day.

As a result of the trial, Israelis’ awareness of the Holocaust became far greater, as did their respect for Holocaust survivors. The integration of Holocaust survivors into Israeli society was affected for the better and even within families, survivors who had never opened up to their own children began doing so. According to many observers, the Eichmann trial also strengthened the Jewish identity of Israelis, especially among the young.

Menachem Begin: We Were All Born In Jerusalem

with Dr. Neil Rogachevsky, Yeshiva University

Before World War II, Brisk (a/k/a Brest or Brest-Litovsk), a city of 300,000 in what is now Belarus, had been for centuries one of the most vibrant centers of Jewish life in the world, known especially for its rabbis and scholars, and, by the early 20th century, also for being an important hub of Zionist politics and activism. All this activity ended swiftly with the war, when the city was one of the first to fall to the Third Reich during its 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. The Nazis not only put an end to Jewish activity in Brisk, they sought to erase the Jews themselves. Over the course of a few days in October 1942, most of the remaining Jews of Brisk—nearly 20,000 in number—were murdered by the Nazis and their accomplices.

Before World War II, Brisk (a/k/a Brest or Brest-Litovsk), a city of 300,000 in what is now Belarus, had been for centuries one of the most vibrant centers of Jewish life in the world, known especially for its rabbis and scholars, and, by the early 20th century, also for being an important hub of Zionist politics and activism. All this activity ended swiftly with the war, when the city was one of the first to fall to the Third Reich during its 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. The Nazis not only put an end to Jewish activity in Brisk, they sought to erase the Jews themselves. Over the course of a few days in October 1942, most of the remaining Jews of Brisk—nearly 20,000 in number—were murdered by the Nazis and their accomplices.

Thirty years later, in 1972, an association of former residents of Brisk by then living in Israel held a commemorative event for the martyred Jews of their home. The keynote address was given by the then-leader of Israel’s political opposition, Menachem Begin, who would five years later become the country’s prime minister.

Born in Brisk in 1913, Begin had lost both of his parents and a brother in the Holocaust. His speech pays tribute to and commemorates not only family and friends, but the community as a whole. Through extensive personal recollection and poetic imagery, Begin evokes a lost world not only of Brisk but of prewar East European Jewry more generally.

Neil Rogachevsky is Associate Director and Research Fellow at the Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought at Yeshiva University, where he researches and teaches Israel studies and political philosophy. His writing has appeared in the Wall Street Journal, Mosaic, Jewish Review of Books, American Interest, Ha’aretz, American Affairs, and other publications. He is currently completing a book on the founding of Israel. He received his BA from McGill University, his MA from the University of Toronto, and his PhD from the University of Cambridge.